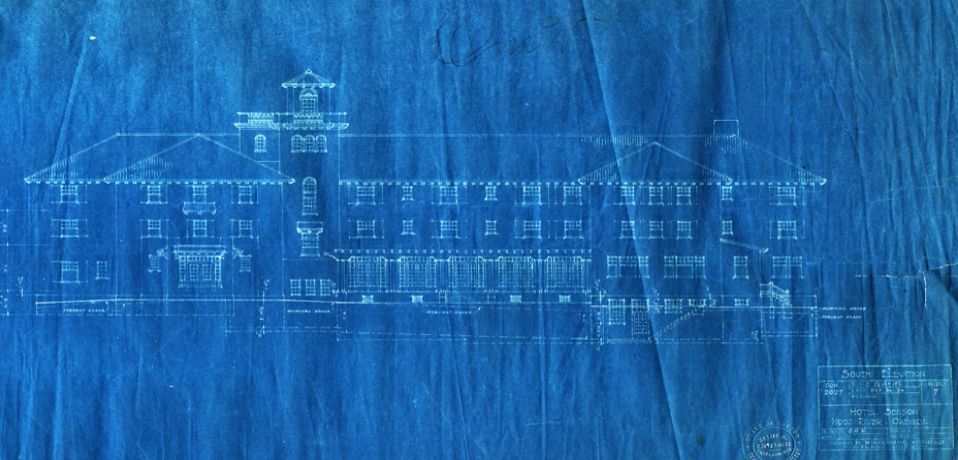

Marrying history and modernity in restoration and reuse

By Cathleen Draper

For years, Vijay Patel drove three hours from Pendleton, OR, to Portland to attend Oregon Restaurant & Lodging Association board meetings. The drive meanders along the Columbia River, passing Hood River, a small city on the precipice of the Columbia River Gorge. It was there, as he drove along the highway, that his eye would be drawn to a Mission-style building perched above the gorge – the historic Columbia Gorge Hotel.

He couldn’t see much from the highway but would take a nearby exit to get a closer look at the building before continuing his trip.

“We moved from England, so I had seen similar structures in England, and my heart just pulled me up there,” said Patel, president of A-1 Hospitality.

He never envisioned he would one day own the property. But Patel has a knack for transforming old hotels into something new – he did it twice in Pendleton. In 2009, he learned that the Columbia Gorge Hotel had closed down, and his friends encouraged him to purchase the building and give it new life. And that’s just what he did.

“I didn’t know I would be the owner of that hotel when I was driving through, or when my friends were talking to me about it,” Patel recalled. “It just happened. It was meant for me and for my family.”

The property – described for the first time in the Lewis & Clark journals – was the site of the Phelps Mill in the 1800s and another summer resort between 1904 and 1920. The resort and surrounding land were purchased by timber baron Simon Benson in 1921, and he oversaw the building of the structure that still stands today.

Originally named the Benson Hotel, the hotel attracted renowned guests – Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge and actresses Shirley Temple and Clara Bow, to name a few. The Benson Hotel fell upon hard times during the Great Depression and changed ownership multiple times until 1952, when it was converted into a retirement home. In 1977, new ownership began a restoration, transitioning the property back to a hotel.

When Patel and his family acquired it in late 2009, it had been closed nearly a year. The grounds, which sit on just over seven acres, were “like a forest,” he said, requiring more than 40 truckloads to remove grass, weeds, and overgrown shrubs. The rooms were filled with cobwebs. But historic charm abounded, and Patel could picture what it could be again.

“My vision was to go in, give it a breath of new life, and turn it around and see what I can do best to keep the history,” he said. “We wanted to keep the old history but at the same time have modern amenities for guests.”

The Rise of Restoration and Reuse

Restoring an old, historic hotel into a modern-day destination and adaptive reuse – transforming an existing building (such as vacant offices) for a new purpose – are growing trends in the hospitality industry.

Often, buildings ready for adaptation and historical restoration exist in places where it’s difficult to embark on a new build, such as in downtown areas, offering the opportunity for owners to utilize a prime location.

It’s the first new hotel on Capitol Hill in 40 years per Meade Atkeson, regional director of operations for Sonesta International Hotels. These projects often receive tax credits and historic preservation credits and are typically more affordable. Commercial real estate and investment firm JLL cited that the cost per key for a full-service urban property was $742,000 in 2023 – putting a 260-room new build at over $192 million.

For example, the Royal Sonesta Capitol Hill – an adaptive reuse in Washington, D.C. – is housed in a former federal office building.

“Adaptive reuse projects typically save 15 percent to 20 percent in costs and schedule compared with new construction,” Atkeson said. “It also considerably reduces construction waste and carbon emissions.”

Restorations and adaptive reuse projects offer more than cost savings and prime locales – they support the local community, tell a story, and provide a sense of place. Historic hotels, Patel opined, contribute to the region’s economy. The restoration process of the Columbia Gorge Hotel revitalized local jobs, enhanced partnerships with local small businesses and vendors, brought special events back to the area, and increased tourism in Hood River.

“There is such a sense of satisfaction when a team has taken a dilapidated building and transformed it into something beautiful,” said Christine Shanahan, principal at HVS Design, a division of AAHOA Bronze Industry Partner HVS. “In doing so, a destination is created where there once was an eyesore. The important part is to highlight the building, not wipe the slate clean. The history, the soul, all that the building has been wants to be brought into the new chapter. Guests are looking for that connection; they are looking for things that go deeper than the surface.”

“More and more, people are connecting to something that feels real. They want to go somewhere that isn’t just the same old, same old, but that truly delivers an experience, and these reuse and renovation projects do.”

The Process of Honoring the Past

To deliver a genuine experience through design, Shanahan looks to the building’s history and its characters.

“We have to become an expert on the building and its history, and so you almost become a student,” she said.

For an adaptive reuse project in Pittsburgh, she and her team leveraged the Columbia University Archives, met with regional archivists, leaned into the historic commission, tracked the building architect’s journey back to New York City, devoured a book written about him, and also captured the history of the local developer and his connection to the steel industry.

The buildings themselves inform design, too.

“You have to listen. You have to look,” said Shanahan. “It’s enhancing what we already have versus just bringing in new.”

On one project, she and her team found a single door. As designers, it served as a clue to keep the building’s story alive, and often, they’ll salvage and repurpose those items in an inventive way. That project also featured two different structures – an office and a printing building, each with different finishes. The local historic commissioner said they must preserve the finishes because of their historical significance related to the buildings’ purposes.

“We thought, well that’s okay,” Shanahan said. “That’s a story in and of itself for the property to share… what those buildings meant in the history of the property.

“You have to become enamored by those conditions and how you can make that a plus for the build out,” she continued. “How can you make that something that is either intriguing, engaging, a learning moment, or just something that is featured.”

When deciding on a design direction for the revitalized Columbia Gorge Hotel, Patel chose a rendering that incorporated modern amenities – including fixing systems that had not been updated since the Eisenhower administration – while making minor, cosmetic changes. And he focused on preserving its iconic elements: The stonework, woodwork, original railings, a grand fireplace, and a functioning, century-old elevator, which only a team member can operate.

“It’s been appreciated, and at the same time, it’s maintaining the history of the building,” Patel said. “We didn’t take over the historical component of the building.”

The property is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which meant the layouts could not change, the existing exterior had to remain the same, and modern upgrades had to match the hotel’s original design. For example, upgrading the wood, single pane windows of the past required approval, and the new windows, though vinyl, are identical in appearance.

Partnerships like these with government and historical organizations are essential to the restoration and design of historic buildings.

But bar none, historic consultants are one of the most important partnerships, according to Shanahan.

“They are really the orchestrator of it,” Shanahan said. “They are the ones who go to the National Parks Service. And a consultant is worth their weight in gold, because they know the lens that the NPS will look at the design through. They know what they’ve gotten approved before and what’s going to be asked of us.”

The second most important, she explained, is a local architect. Partnering with an area expert can assuage owners and city officials, and their perspectives can make the process easier, especially if an architect has done a restoration or reuse in the same area before.

Local historical societies and government officials play a part, too. They advise on the history of the building and the surrounding community, providing invaluable context. Often, Shanahan works with mayors, who serve as advocates for a historical restoration project.

Working With What You’ve Got

While historic properties offer a unique opportunity to highlight rich history and cultivate a unique stay, restoring and adapting century-old buildings comes with challenges.

When Patel embarked on the Columbia Gorge Hotel renovation, overgrown grounds and cobwebs were just the start. After opening the floors and walls to determine what work the building’s insides needed, he discovered century-old surprises. The wood had rotted, and the plumbing was rusted and blocked. Temporary fixes abounded.

“It’s like looking at an old classic car,” he said. “You look at the colors and the condition, and you fall in love, and then you discover the previous owner used duct tape to cover issues.”

Adaptive reuse and restoration projects always bring complexity, Sonesta’s Atkeson said. But the redevelopment of the Royal Sonesta Capitol Hill required particularly careful coordination. The original building was concrete framed with deep floorplates and a wedge-shaped footprint, which became the primary drivers of its design.

“Because guestrooms must have access to natural light, the depth of the office floorplates posed a significant challenge. This ultimately led to one of the project’s most transformative moves – cutting two atriums through the existing slabs to bring daylight deep into the building and enable additional guestrooms with windows.”

Cutting the two atriums meant creating significant openings through concrete slabs, which required structural, architectural, and construction alignment to maintain the building’s integrity.

They also gutted the building down to its structure, removed the entire concrete façade, and added two new stories and a penthouse, all while installing new mechanical systems, life-safety upgrades, and enclosure requirements. The changes helped to reconcile the 1970s construction with modern standards. The redeveloped building is mixed use, too, which meant Atkeson and his team had to design hotel-specific systems in a framework that incorporated flexibility for future office and retail tenants.

“The complexity of the redevelopment ultimately helped elevate the building’s performance, contributing to LEED Gold Certification and WELL Certified Core and Shell,” Atkeson said.

Meeting modern safety requirements while satisfying guest expectations in a reuse and renovation project is a constant push-and-pull for Shanahan. Historic buildings rarely have the power hubs guests expect in new builds and adding them can mean damaging or removing design elements of significance. These structures often lack accessibility features such as ramps, requiring Shanahan and other designers to thoughtfully integrate ADA-compliant solutions into their design plans.

On one project, an elevator didn’t meet gurney code – meaning that if a guest needed to be transported on a stretcher, none of the elevators could accommodate it. This issue ultimately required the team to modify an existing elevator to meet the necessary safety standards.

Sometimes, consultants on the project come through and determine where safety alarms and fire annunciators should go, but “they don’t see the wall the way we see it. They don’t see the historic elements the way we embrace them,” Shanahan said.

For Patel, the Columbia Gorge Hotel renovation was more than a restoration – it was a stewardship responsibility.

“We’re always running buffer to the building. And then the challenge becomes, where? Code versus history is the ongoing saga of every one of these buildings.”

Though challenges often abound, owners taking on a historic renovation or adaptive reuse must keep the end goal in sight and embrace the speed bumps.

“Don’t give up, stay positive, and make sure everything is done correctly,” Patel said. “I’ve put in so much time behind that asset, and if I didn’t give that time, the hotel wouldn’t be what it is today. If anybody wants to get into this kind of project or asset, it has to be for your love for it.”

Images: Columbia Gorge Hotel, Royal Sonesta Capitol Hill

Leave a Reply